History is an escape, historical fiction arguably more so. Today, let’s stick to the factual and I’ll whisk you away from the culminating frenzy that is the US Presidential Election, away from voter suppression and a partisan press, to 1864, a time of honour and common decency in the conduct of a fratricidal civil war; a time of extreme crisis. Thousands of enlisted Americans were dying on the battlefields and in the army hospitals every week but, what do you know, it was an election year.

In the fourth year of the conflict, there was talk of suspending the presidential election altogether, but Lincoln wouldn’t have it, claiming that postponing a wartime poll would allow the rebels to ‘fairly claim to have already conquered and ruined us.’ This was no small deed on Lincoln’s part. The Union armies were stalled in the east and moving at a snail’s pace in the west. It was widely believed in the country, in his still young Republican party and by Lincoln himself, that it was almost impossible for him to be re-elected. There wasn’t the elaborate and voracious polling industry that we have today, providing false or tilted reassurance to both sides, but Lincoln knew the score. Nobody had been re-elected for three decades. The country was weary of sacrifice and suspicious of Lincoln’s change in the war’s aims to overtly include emancipation. He only stood again, he said, because the country shouldn’t be ‘swapping horses in the middle of the stream.’

‘Events, dear boy, events,’ a British prime minister would say a century later in reference to the lot of a government. In this case, a positive event broke for Lincoln; a great victory won by General Sherman’s army in early September 1864, two months before the election. Sherman wired Lincoln. ‘Atlanta is ours, and fairly won.’ With that city taken in the heart of Georgia, the people of the north could suddenly see the other side of the stream and they believed that Lincoln was the right horse to get them there. All the youthful Republican party needed to do was run a clean election, but it doesn’t hurt to make sure.

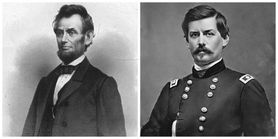

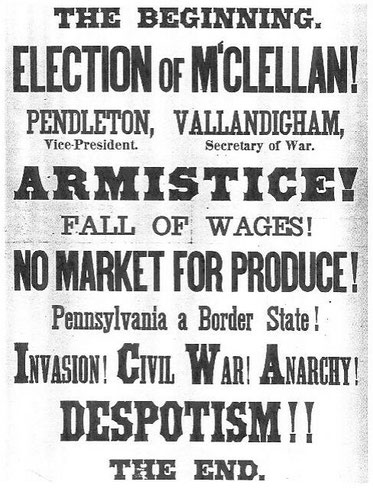

In those blessed days it was considered unseemly for the presidential candidates to campaign, so Lincoln and his adversary, General George B McClellan – running on a peace ticket - stayed home and let their respective representatives get down in the ditches of democracy. Papers were the only media and there was little or no tradition of an unbiased press to live up to. Lincoln’s campaign manager was the editor of the New York Times. The editor of the New York Tribune, Horace Greeley, went out on the stump for Lincoln. The editor of the New York World worked with McClellan. Beyond the papers, Lincoln tacitly approved more or less any tactic available to secure the vote. Government workers were required to give ten percent of their salaries to the Republican party. They were granted election day off to ensure they had time to vote for Lincoln. In the run up to the election, the same civil servants had been used to send out Republican campaign literature.

There was the difficult question of whether the soldiers themselves should be allowed a ballot. Never had so many men – the only sex eligible to vote – been under arms. The America we know today was still under construction in the 1860s, the war being fought to determine if that was to comprise of one nation or two. Large swathes of the west were yet to be formed into states and admitted to the Union. The eleven seceded Confederate states were out of the election of their own volition, leaving only twenty-five states to participate. In those twenty-five there was a patchwork of fresh legislation pertaining to soldiers voting. Some states had enacted laws for them to vote through their regiments wherever they may be stationed or fighting. Other states allowed soldiers to vote only if they were in their home state. Some made no provision for them at all.

Where soldiers were allowed to vote, the suppression and intimidation wasn’t subtle at all. In some cases, expressing support for McClellan could get you put on punishment duties, court-martialled or even dismissed. In other regiments, where they had to return to their own state to vote, those putting a hand up to say they would vote Republican were given furloughs to go home, while Democrats were kept in camp. No vote for them. There was little secrecy in how you voted in the 19th century. Parties printed their own colour coded ballots; you would simply collect one from a party representative. Everyone on hand knew exactly how you were voting. And going against the prevailing sentiment for Lincoln would have been a gutsy move. There were court challenges on soldier voting right up to the Supreme Court. Is this starting to sound familiar?

These shenanigans didn’t really matter in the short term. Sherman’s victory ensured that Lincoln won by a landslide. The war was won within six months. Lincoln was a sound horse, but assassinated almost at the moment of victory. But in the longer term, as is so often the case with changes brought in during the civil war, the ability for soldiers to vote bore fruit in the future. Eventually all soldiers on duty, even those outside the re-established Union, were able to post an absentee ballot. That in turn led to civilians being able to do the same. In 2020, I’m privileged to know many Americans casting their votes from the UK. And mail in voting is happening in unprecedented numbers. The outcome of the war had a more fundamental impact of future elections though. Before the war only very few free blacks were allowed to vote, even in the north. In 1870, the 15th amendment prohibited states from denying a male citizen the right to vote based on ‘race, colour or previous condition of servitude.’ Women would have to wait a lot longer for the franchise.

We can look in on the past, but we can’t truly escape the present. We’re in another time of crisis and accelerated change. Not just America, but globally. What is happening right now in our world that will steer our children’s future?

Battle Town (short story)

Write a comment

Jeff Houston (Tuesday, 03 November 2020 17:30)

Pard, as always, succinct, to the point and well said indeed!

Leigh (Tuesday, 03 November 2020 19:19)

Very interesting read. Any insight into how the world might be different if McClellan had won?

Sounds like he had little chance of success judging by Lincoln's use of federal resources.

Richard Buxton (Tuesday, 03 November 2020 20:19)

It all swung on the war, Leigh. If Atlanta hadn't fallen then it's very likely McClellan would have won. He was what was called a 'war democrat' but had his hands tied by the peace faction in his party in order to get the nomination. So he would have been obliged to try and negotiate a peace. If that had resulted in the Confederacy being recognized, I personally doubt it would have held together for too long. They were too fractious and slavery would have made them a pariah in the evolving world community. They'll be books hypothesizing on all this.